Author: Keith Nurse, Senior Fellow, Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados; World Trade Organization Chair, University of the West Indies; Expert Member, UN Committee for Development Policy.

Email: [email protected];

Introduction

The Trinidad and Tobago carnival is one of the largest and most well known festivals in the Americas along with the famous Rio Carnival in Brazil and the Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Trinidad and Tobago also boasts of having one of the festivals with the highest level of local participation. It is estimated that over ten percent of the population is directly involved in terms of costuming, singing, playing instruments and producing the events.

Trinidad and Tobago’s carnival has generated many offspring and inspired the structure of several carnivals throughout the Caribbean region (e.g. Jamaica, Barbados, St. Vincent and St. Lucia). The carnival also has been exported outside the region and is to be found in close to one hundred Diasporic Caribbean Carnivals, making it the world’s most globalized festival as well as the festival with the highest level of economic impact in global cities like Toronto, New York and London.

Carnival and Festival Tourism

The carnival festival is also the top draw card for tourism arrivals in Trinidad and Tobago. More people travel to Trinidad during the carnival season than at any other time in the year. For example, February is the month with the largest number of arrivals, including the highest number of hotel, private and guesthouse visits.

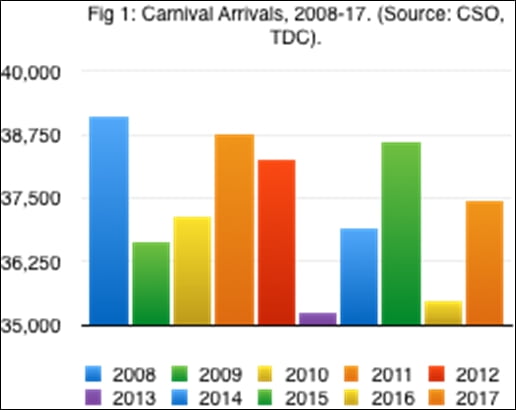

Carnival visitor arrivals grew rapidly during the period 1997 (27,000) to 2006 (42,000) and peaked just prior to the onset of the global economic crisis which affected key source markets. From 2008 arrivals have fluctuated between 35 – 39,000 visitors suggesting that the festival tourism impact has reached a plateau.

Carnival arrivals continue to be a key driver of tourism and creative industries expansion. Tourist arrivals for the Carnival consistently account for over 12.0% of total annual arrivals and visitor expenditure for the three-week period. A large share of repeat visits from Diaspora, regional and cultural tourists, drives this impressive economic performance.

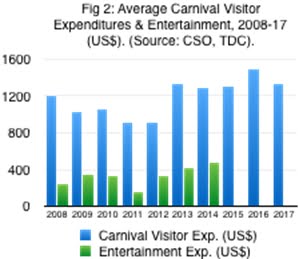

In terms of visitor expenditures, it is estimated that the 2004 total carnival visitor expenditure was approximately US$30 million, three times the 1997 figure. Since 2004 expenditures have climbed to a peak of approximately $51 million in 2016, with average visitor expenditure at close to TT$10,000 or US$1,450.00. In 2017 the estimated total visitor expenditure is measured at US$50 million (see Figure 2).

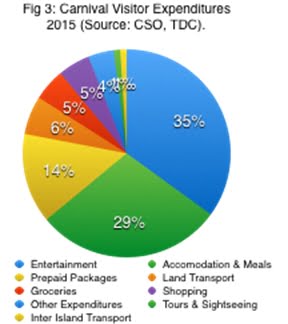

Carnival visitor arrivals have also had a significant impact on the entertainment and creative economy. Figure 2 shows that average expenditure on entertainment account for on average one-third of total carnival visitor expenditures with the exception of 2011, which experienced a dip in visitor expenditures. The entertainment share of carnival visitor expenditures has risen to as much as 30-35% in 2015 surpassing accommodation and meals expenditures which is estimated at 29% (see Figure 3).

Carnival and Trade in Services

The Carnival is traditionally associated with Calypso, Steelpan and Masquerade and on account of the festival economy these artforms have tapped into the tourism and export markets which provide an avenue of entrepreneurship and employment for designers. These activities also generate trade in services. The major mas bands produce costumes for bands in diasporic Caribbean carnivals like Miami, New York, London, and Toronto as well as regional carnivals like Cropover and Jamaica Carnival. These exports involve a mix of high-end designer skills along with technical expertise in sewing, wirebending, fabricating and so on.

The Carnival indirectly creates thousands of jobs in a host of ancillary industries. Telecoms (e.g. cell phone rentals), ground transportation, auto rentals, catering, tour operations, book publishing, advertising, handicraft sales and the clothing industry. From this standpoint, the Carnival is one of the key pillars of the Trinidad and Tobago economy and deserves to be managed as such.

Services trade is manifested in different modes. Table 1 outlines the various modes of services supply as it would apply to the creative sector. Mode I is cross-border supply which refers to services that is transmitted via some form of telecommunications, for example, sound engineering (a soundtrack) or design services (e.g. costume designs) that are sent to a client via email. This is an area where Trinidad and Tobago has expanding capabilities on account of the importance of the regional carnivals and the diaspora as markets in the EU, US and Canada.

Consumption abroad (Mode II) is where consumers from one country travel to use services in another country. This involves tourism related activities such as festival tourism which is captured in the above analysis. This is the largest source of earnings for the carnival services trade with 2017 tourism expenditures at US$50 million.

Mode III refers to a firm establishing “commercial presence” in another country to provide a service, for example, setting up a radio station or a booking agency. This is an area where trade in services has been the weakest in spite of the importance of the diasporic markets.

Mode (IV) speaks to the movement of natural persons, for example, a music band on tour. This is the area which accounts for the second largest share of the services exports for the carnival sector. The exact earnings are virtually impossible to measure given the weak data capture in this area.

Table 1: Modes of Supply in Trade in Creative Services

| Mode I:

Cross-border supply |

Supply of services from one country to another, for example, sound engineering services or Mas design services transmitted via telecommunications. |

| Mode II:

Consumption abroad |

Consumers from one country using services in another country, for example, cultural, festival and heritage tourism. |

| Mode III:

Commercial presence |

A company from one country establishes a subsidiary or branch to provide services in another country, for example, setting up a booking agency. |

| Mode IV:

Movement of natural persons |

Individuals travelling from their own country to offer services in another, for example, an artist or band on tour. |

This problem is not restricted to Trinidad and Tobago. Data on trade in creative services is very weak or non-existent because most developing countries do not capture data on the extended balance of payments in services. In addition, because industry associations do not adequately represent the sector it is very difficult to get an appreciation of the volume or value of trade in creative services. The only area for which there is any reliable data is in Mode II activities (consumption abroad) such as the expenditures of carnival visitors which can be categorized as festival, heritage and cultural tourism.